Modelling Static Loading

The static load on a bridge exerted by HG traffic depends on two factors:

- the number of HGVs on the bridge at one time, and

- the weight of the vehicles.

Both of these factors are random variables: they can only be modelled in statistical terms. The weight of a randomly selected vehicle cannot be known in advance, however, we can say that it will fall into a given distribution. We use the Conditional Axle Load (CAL) model to quantify this statistical variation of loads applied to the bridge.. The number of HGVs simultaneously on the bridge depends on whether HGVs are evenly distributed among other traffic, moving in convoy, or in closely packed convoys that are stationary due to congestion. It will also depend on the diurnal and weekly traffic patterns. We quantify these effects using our Traffic Flow Model. Both CAL and traffic Flow models are stochastic, accounting for both random and deterministic factors.

The CAL and Traffic Flow models form the basis of our statistical analysis. They are combined into the load model, which along with a statistical model of the structural element in question are passed to the simulation engine. This will give an estimate of the likelihood the element will fil within the defined time period. In the following subsections we will describe how the load model is derived from BWIM data and the method by which we combine load and structral models within a probablistic framework.

Finding the GVW and Traffic Flow Distributions

A BWIM system gives the following information:- list of vehicles

- their speed

- their weight

- the time they crossed the bridge.

Statistical Analysis Method

The safety of a bridge is assessed by examining individual structural elements. Like the loading of the bridge, the strength of a given structural element is also a random variable and is also best treated in probabilistic terms. It follows that any prediction about the failure of the element will also be probabilistic.

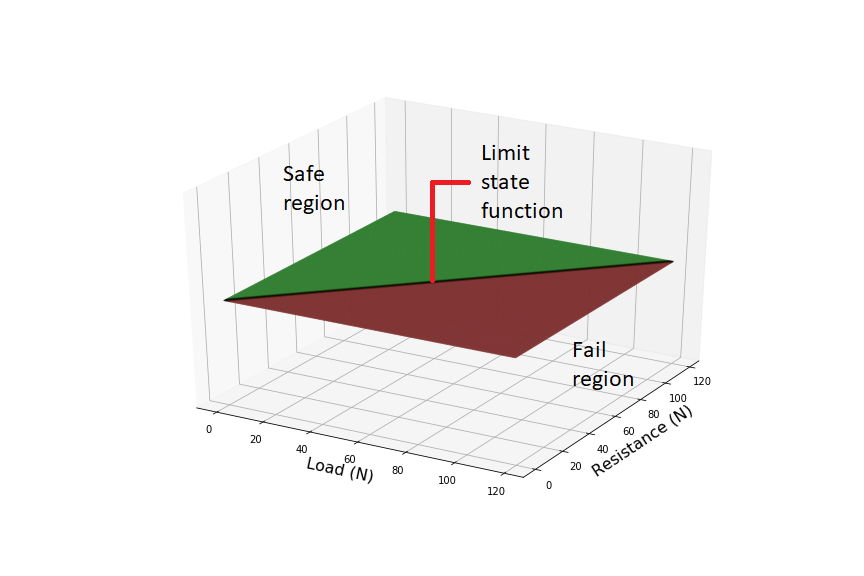

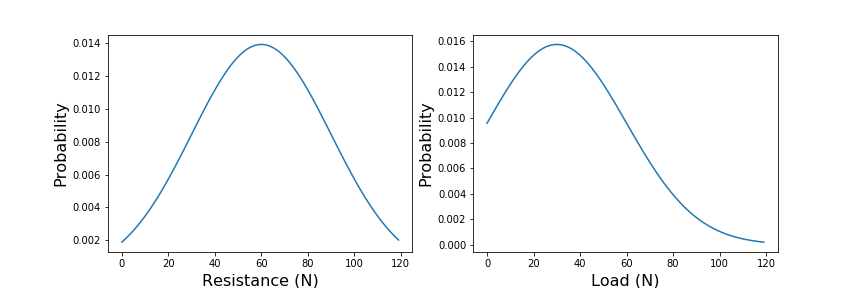

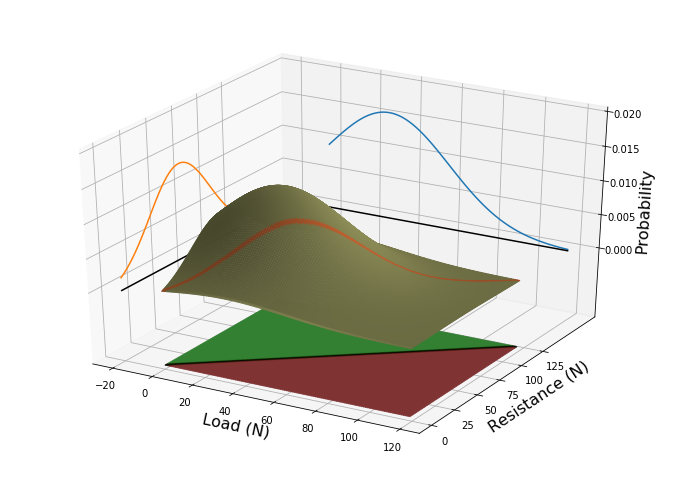

Consider a trivial example: a beam of resistance R, is loaded with a force S. If the load exceeds the resistance, i.e. R ‹ S, then the beam will fail. We can plot all the possible combinations of strength and load, opposite. The failure region, i.e. those combinations of R and S for which the beam will fail, lie on one side of the line R-S=0, and the safe region lies on the other. We call this line the Limit State Function.

Now, assume that we know that structural elements from the same batch have a statistical distribution of resistances, centred around 90k Newtons (left). Furthermore, we know from our BWIM measurements that most loads occur around 60k Newtons, but occasionally we will get a higher load. What is the probability that the beam will fail? To know this, we must consider the joint probability of R and S (right). The probability of failure, is the sum of probabilities in the failure region. In more mathematical terms, this is the integral of the joint probability function over the region bounded by the limit state function.

In this trivial example, it is easy to understand what is happening, but surprisingly difficult to estimate the probability of an event intuitively. Things get more complicated if there are many variables—as there usually are, or if they are correlated with one another. For this reason, in the early nineties we developed the Variables Processor software library. This remains at computational core of many of our subsequent applications, the interested reader is referred to [2].

Summary

With our models of vehicle weight and traffic flow, and data from BWIM, we can predict the likely loads on a bridge. With our structural engineering expertise we select a series of critical structural elements, and estimate the proability of failure as a function of load. The Load Model and Strtuctural Model are then passed to our Stochastic Simulation Engine which will the estimate the likelihood of the element failing.